At the time of contact with Europeans in the 16th century, the Guale, the Timucua, and the Apalachee peoples in Florida formed part of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, a rich Native American exchange network with identifiable motifs and sophisticated patterns of symbolic and artistic expression. This Complex flourished in the Mississippi Valley from 900 C.E. until 1500 C.E. and extended north and east into vast regions of the land.

For the Spanish intruders stationed at the garrison of St. Augustine founded in 1565, “La Florida” was a harsh frontier that did not yield returns other than holding on to a strategic location. Its failure as a profitable colonial economic enterprise notwithstanding, a vigorous missionary effort was launched in the land, with the Franciscan order at its helm. Not without great toil and setbacks, the Friars Minor established mission systems that lasted almost two centuries and extended from the mid-Georgia coastline, south to St. Augustine, and westwards, reaching Tallahassee.

Tragically, due to epidemics, colonial exploitation by the Spaniards, and the ravages of commodified slavery introduced by the English, the missionized Guale, Apalachee, and Timucua almost disappeared as a people by 1763. And yet, the legacy of their transcultural competence as they negotiated the globalizing epistemology of Christianity while preserving core aspects of their indigenous identity deserves to be explored, better known, and remembered.

This exhibition was curated by Viviana Díaz Balsera, Professor of Spanish for the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Miami, and Arthur Dunkelman, Curator of the Jay I. Kislak Collection for Special Collections at the University of Miami Libraries.

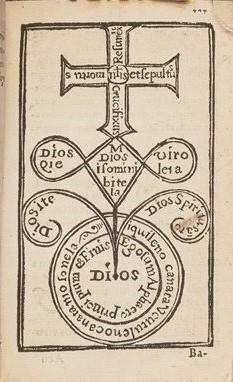

Hieroglyph from Tercero Cathecismo by Fr. Gregorio de Movilla, 1635 from the NY Historical Society interspersed with a map of La Florida from Theodor De Bry

Hieroglyph from Tercero Cathecismo by Fr. Gregorio de Movilla, 1635 from the NY Historical Society interspersed with a map of La Florida from Theodor De Bryvdiaz-balsera@miami.edu

Shatha Baydoun

- History and Modern Languages & Literatures Librarian

- sbaydoun@miami.edu

- (305) 284-6027

Arthur Dunkelman

- Kislak Collection Manager

- adunkelman@miami.edu

- (305) 284-2560

Below are examples of these objects from the exhibition“From Precontact to Shatter Zone: Exploring Florida Legacies” at Richter Library (April 7-September 30, 2022).

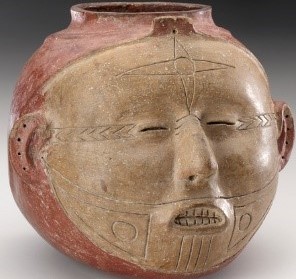

This is a fine example of a unique SECC ceramic tradition. Believed to be a portraiture modality, head vessels are thought to represent lifeless warriors, venerated ancestors, or leaders. The tattoos on the face may suggest ritual personification of a mythical being by the portrayed individual when he was alive.

Image courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian

This masterfully incised gorget is believed to be a cosmogram. The cross has been interpreted to represent the four logs feeding the sacred fire, the circle to refer to the sun in the Above World, and the crested birds, other-than-human beings, are associated with weather powers and the four cardinal directions

Text and image courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian

Located near Tallahassee in Leon County and flourishing between 1100 and 1400ce, Lake Jackson was an important Mississippian ceremonial center boasting mound construction, elaborate maize agriculture, and sustaining the most politically complex culture in precontact Florida. Sophisticated burial art objects such as repoussé copper breastplates, engraved shell gorgets, pendants, and hair ornaments are found in its mounds. They show style similarities with comparable objects in major sites in the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC) network such as Spiro, Moundville, and Etowah, evincing a dynamic exchange activity, especially with Etowah.

Southwards along the Florida Gulf Coast is the Key Marco site. Its excavation by Frank Hamilton Cushing in 1896 is one of the major events in North American archaeology. Conducted in a muck pond of less than one acre of extension Cushing called “Court of Pile Dwellers,” the excavation yielded more than 1000 wooden and cord artifacts, as well as hundreds of objects in shell and bone. The artifacts were deposited anywhere from the 700’s CE to the contact period in the 1500s.

Below are examples of these objects from the exhibition “From Precontact to Shatter Zone: Exploring Florida Legacies” at Richter Library (April 7-September 30, 2022).

Kneeling Key Marco Cat, 1400-1500 CE. Key Marco site.

Masterfully carved in dark-colored hardwood, the best-known figure of the Key Marco site and one of the finest pre-contact Native American ceremonial art objects in North America, is only six inches tall. It has been pointed out that the statuette is carved in the likeness of Florida panthers and that in Native American Southeast cosmography, panthers were associated with the watery Underworld. Because the artist of the statuette was most likely a Calusa, the association of this humanoid panther-god figure with the powers of coastal waters, is plausible.

Image courtesy of the National Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology

Sea-Turtle Carved figurehead, 1400CE. Key Marco site. Originally painted in black, white, blue, and red.

When the object was removed from the muck pond, the colors soon began to vanish. To preserve a record of designs and pigmentation, expedition artist and photographer Wells M. Sawyer painted on-site a series of watercolors of masks and figureheads before all colors and painted lines faded. This is the only extant visual documentary evidence of these aspects of the figure.

Image courtesy of Penn Museum

The first permanent Spanish settlement in La Florida was established in St. Augustine in 1565 by the frightening Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, sent by Philip II to clear the land from the French Huguenots. The garrison of St. Augustine would be a harsh, costly coastal frontier that would yield no returns other than its strategic location to keep European powers away. Its failure as a profitable colonial economic enterprise notwithstanding, a vigorous missionary effort was launched in the land with the Franciscan order at its helm. With significant toil and setbacks like the indigenous uprisings of 1574, 1597, 1647, and 1656 against Spanish oppressive treatment, the friars’ constant quarrels with Crown officials, and the dire living conditions of La Florida, the Franciscans established missions among the Guale, the Timucua, and the Apalachee peoples.

At the time of contact, the Guale lived along the Georgia coast and the barrier islands. They were organized in approximately six chiefdoms, were mound builders, and spoke a distinctive Muskogean language. The Timucua had flourished in southeast coastal Georgia and northeast coastal and northern inland Florida. There were approximately 35 simple Timucua chiefdoms when the Europeans arrived. The third group of people missionized by the Franciscans was the Apalachee, who inhabited northwestern Florida in the area of present-day Tallahassee. They were horticulturalists and had shared various aspects of the rich Mississippian culture such as ceremonial mound-building, and participation in exchange networks of highly crafted goods. The Franciscan missions among the Guale, the Timucua, and the Apalachee lasted almost two hundred years.

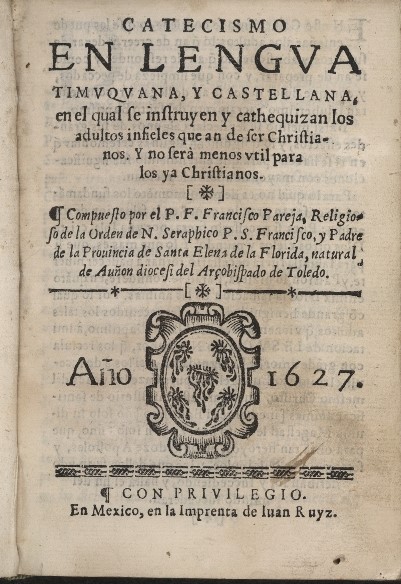

With the assistance of native speaker intellectuals, the friars learned the indigenous languages and set them down to writing. There are nine extant imprints in Spanish and Timucua produced during the first three decades of the seventeenth century, making it the first recorded indigenous language in the present-day United States. These bilingual imprints amount to a robust body of work that tells us important stories about cultural exchanges between the friars and the Timucua during the mission period. An extant letter in Apalachee written to Charles II in 1688 by Apalachee chiefs requesting a fort to protect the missions in the region evidence that the Apalachee language was also set down to writing. However, no other documents in Apalachee or Guale have been recovered. Some of the Timucua-Spanish bilingual imprints as well as the letter from the Apalachee chiefs are highlighted in this exhibition.

Tragically, due to epidemics, colonial exploitation by the Spaniards, and the ravages of slave raids by the English and their indigenous allies, the missions had disappeared by 1763 when the Spanish swapped Florida for Cuba with the English. But the transcultural competence of the Guale, Timucua, and Apalachee as they negotiated the globalizing epistemology of Christianity while preserving core aspects of their indigenous identity is a significant element in Florida’s early modern legacy that deserves to be explored, better known, and remembered.

Below are examples from the exhibition, “From Precontact to Shatter Zone: Exploring Florida Legacies” at Richter Library (April 7-September 30, 2022).

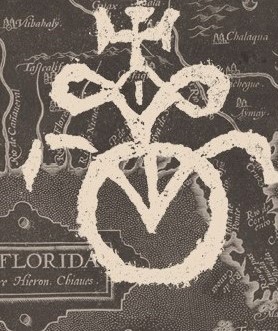

Hieroglyph with Inscriptions in the Tercero Cathecismo

This hieroglyph with inscriptions in Timucua, Latin, and Spanish encoding Christian doctrine appears in the Tercero Cathecismo by Fr. Gregorio de Movilla, published in 1635 in Mexico City as part of his larger volume Explicacion de la Doctrina.

Image courtesy of the New York Historical Society

Keynote by Dr. Jerald T. Milanich. Curator Emeritus of Archaeology at the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida

“Indians and Europeans; Documents and Artifacts: Discovering the Two Hundred Year History of Spanish Florida’s Missions”

Session 1 Indigenous Political Formations and Identities in Pre-contact and Contact Florida: The Archaeological Evidence

Moderator: Dr. Will Pestle

Complicating the Indigenous Landscape of South Florida Prior to Spanish Contact: Tequesta and the Matecumbe Materialities

Dr. Traci Ardren, University of Miami

Centering Mocama Communities and Indigenous Landscapes in a Time of Spanish Missions

Dr. Keith Ashley, University of North Florida

Moderator: Dr. Pamela Hammons

Translator, Perpetrator: Unpacking the Difficult Cargo of Florida's Franciscan Verse

Dr. Thomas Hallock, University of South Florida.

A Franciscan Tells his Tale of Captivity in Oré’s Account of the Martyrs of La Florida (pre-recorded)

Dr. Raquel Chang-Rodríguez, City University of New York Graduate Center

Lunch break: 11:45am-12:45pm

Moderator: Dr. Susanna Allés-Torrent

A Que vamos à la Yglesia? Liturgical Performance and Franciscan Identity in Fr. Francisco Pareja’s 1628 Catecismo

Dr. Timothy Johnson, Flagler College.

Performing a Hieroglyph in La Florida: Gregorio de Movilla’s Tercero Cathecismo for the Timucua

Dr. George Aaron Broadwell, University of Florida at Gainesville.

Dr. Viviana Díaz Balsera, University of Miami

Moderator: Dr. Logan Connors

Decolonizing “Conversion:” Indigenous Constructions of Spanish Catholicism in the Native South

Dr. Denise Bossy, University of North Florida.

Apalachee Resistance and Resilience in Colonial Sources

Dr. Alejandra Dubcovsky, University of California at Riverside.

The Apalachee in West Florida, 1704-1763

Dr. John E Worth, University of West Florida.

5:00-6:00pm Closing Remarks by Chief Arthur Bennett of the Talimali Band Apalachee Indians of Louisiana

Presenting Chief Arthur Bennett: Dr. John E. Worth

Ethridge, Robbie, and Charles Hudson. Transformation of the Southeastern Indians, 1540-1760. University Press of Mississippi, 2002.

Reilly, F. Kent, and James Garber. Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms Interpretations of Mississippian Iconography. 1st ed., University of Texas Press, 2007.

Yaremko. (2016). Indigenous Passages to Cuba, 1515-1900. University Press of Florida.

Milanich, & Bennett, C. (2009). Laudonniere & Fort Caroline: History and Documents. University of Alabama Press.

Fundaburk. (2000). Southeastern Indians Life Portraits: A Catalogue of Pictures 1564-1860. (1st ed.). University of Alabama Press.

Granberry. (1993). A Grammar and Dictionary of the Timucua Language. The University of Alabama Press.

Weitzel. (2002). Journeys with Florida's Indians. University Press of Florida.

Milanich. (1995). Florida Indians and the invasion from Europe. University Press of Florida.

Milanich. (1996). The Timucua. Blackwell Publishers.

Milanich, Sturtevant, W. C., Pareja, F., & Jay I. Kislak Reference Collection. (1972). Francisco Pareja's 1613 Confessionario; A documentary source for Timucuan ethnography. Florida Division of Archives, History, and Records Management.

Loucks. (1980). Political and economic interactions between Spaniards and Indians: Archeological and ethnohistorical perspectives of the mission system in Florida.

Worth. (1995). The struggle for the Georgia coast: An 18th-century Spanish retrospective on Guale and Mocama. American Museum of Natural History.

A collection of materials from the National Park Service.

Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum

Home to more than 180,000 unique artifacts and archival items. Come and learn about the Seminole people and experience their rich cultural and historical ties to the Southeast and Florida, as they have made Big Cypress their home since creation.

The Seminole Tribe of Florida

Learn about Florida's largest tribe with the official website of the Seminole Tribe of Florida.

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida

The official website of the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida.

National Museum of the American Indian

Preserves and studies the life, languages, literature, history, and arts of Native Americans.

Native Americans in Florida

A bibliography that lists some of the published works in the State Library on Native American history in Florida.

Aucilla River Prehistory Project

An archaeological and paleontological project excavating a particularly rich series of deposits that yielded ancient megafaunal remains in association with Paleoindian artifacts.

Shatha Baydoun

- History and Modern Languages & Literatures Librarian

- sbaydoun@miami.edu

- (305) 284-6027

Arthur Dunkelman

- Kislak Collection Manager

- adunkelman@miami.edu

- (305) 284-2560